Understanding FOMO

We all feel it, but is it what we think it is?

A couple years ago, I did a profile of Garance Doré for Air Mail. It was a wee dive into this recovering fashion influencer who was undergoing a Great Life Reset. She had given up the shows, the posing, and flailed through depression and disorientation before moving to Somerset with her new husband. Minus the husband part, and the pressure of a large social media following, I could relate. I, too, had chucked a fashion-y media career to navel gaze in a pasture. I, too, had a pile of improbable shoes I would likely never wear again. I, too, had a ton of status anxiety and a lot invested in making my new life seem just right before I really knew what it was.

We met up in Paris, and I was charmed. Her story made me feel like maybe we were an avant-garde: ladies of a certain age saying goodbye to all that and going into nature to muddle through our insecurities. It was reassuring.

Great Life Resets play hell with your insecurity. You’re looking at a void of newness with only faith in yourself for reassurance because you can’t rely on context clues or expertise for the rest. Who among us has that much self-belief? (By “us” I mean non-malignant narcissists.) Anyone else you encounter who is on a parallel track is a godsend. “Oh, you too?” came up many times in our chat.

I subscribed to Garance’s Substack as part of researching that story. It’s a first-person journal of her life, and I’ve kept reading long after I didn’t need to pay attention anymore because I admire her guileless and breezy way of being honest and raw while monetizing earrings and shoes. (No shade; get paid, girl.) When you do first person writing from a position of relative comfort, whining is an ever-present pitfall, and Garance has a comedic touch when she falls in. She nails the difficult balance of confessional and aspirational without coming off as too self-serious or clueless. It’s a friendly pleasure.

And then she wrote about her decision to bail on the countryside, move back to Paris and start going to fashion shows again, and I thought, “Oh shit.” My pretend other half had to admit she wasn’t happy in idyllic rurality. “Good for her,” I thought. It’s important to be supple in life and course correct. But what about me?”

We live very different lives, have different resources, and are completely different people. Duh. But I knew there was something to parse in that “Oh shit.”

I guess urban fashion media life isn’t the devil for ladies of a certain age who have known the countryside. Fashion shows are still going on, even if I am no longer occasionally attending them. My decision to leave my life was more situational and need based than a premeditated plan and it has at times felt like going into exile. Did a part of me still want to be back in those shoes again too? Was that “Oh shit” FOMO? Christ.

FOMO, which is “fear of missing out” for my Boomer readers (love you guys), is dreary to admit to. We absolutely all suffer from it and most of the time we castigate ourselves when we recognize it. We’re supposed to be self-sustaining nonconformists with rock solid True Norths, and worrying about what everyone else is doing is simply a manifestation of unhealed insecurity. It’s lemming-y and we’re heroes and cowboys so we don’t do that. We aren’t supposed to be the herd, we’re supposed to drive the herd.

Except humans are hardwired to be part of a group. We all know how useless human babies are, and how much of a village it takes to raise one. We constantly refer to the tribal nature of our species as an established fact. So isn’t FOMO also how we naturally feel when we aren’t with the others? We have solid biological and cultural reasons for it.

After a few long stews trying to find something to miss in the life I gave up—I was antisocial, depressed, in a dysfunctional couple and not exactly living life to the fullest in Paris—I went back out a few weeks ago to spend some time with a pal in an Air Bnb near my old neighborhood of Pigalle. We thought we’d pop into the newly redone Notre Dame, and as we walked down, I said to him, “Work is going well. I could probably swing getting a place here again if I really wanted to.” I was testing the idea, on location, in real time. And then we got to the esplanade in front of the church, and it was jam-packed with people queueing up and we looked at each other and said, “Oh fuck no.” Notre Dame isn’t going anywhere.

Just a few minutes after that, as we elbowed our way back towards the relative peace of the rue de Rivoli, I said, “Oh fuck no” to coming back to Paris too. It wasn’t just the throngs and the rudeness. It was that I knew all those streets and they were great for memories, but I am not looking for anything in them anymore except somewhere new to eat.

Still, reading about Garance going back into the lion’s den that temporarily robbed her of her sanity, it continued to nag me as I half-assedly combed through the thirty million press releases that clutter my inbox every week. They speak of new hotels, new products, new designers. Very few of them interest me. They represent my life as a journalist, which is almost as behind me as my life in Paris. I still do the occasional story, but it is no longer how I earn the majority of my bread. Now I do that ghost writing.

OK this was the pain point. I knew there was one.

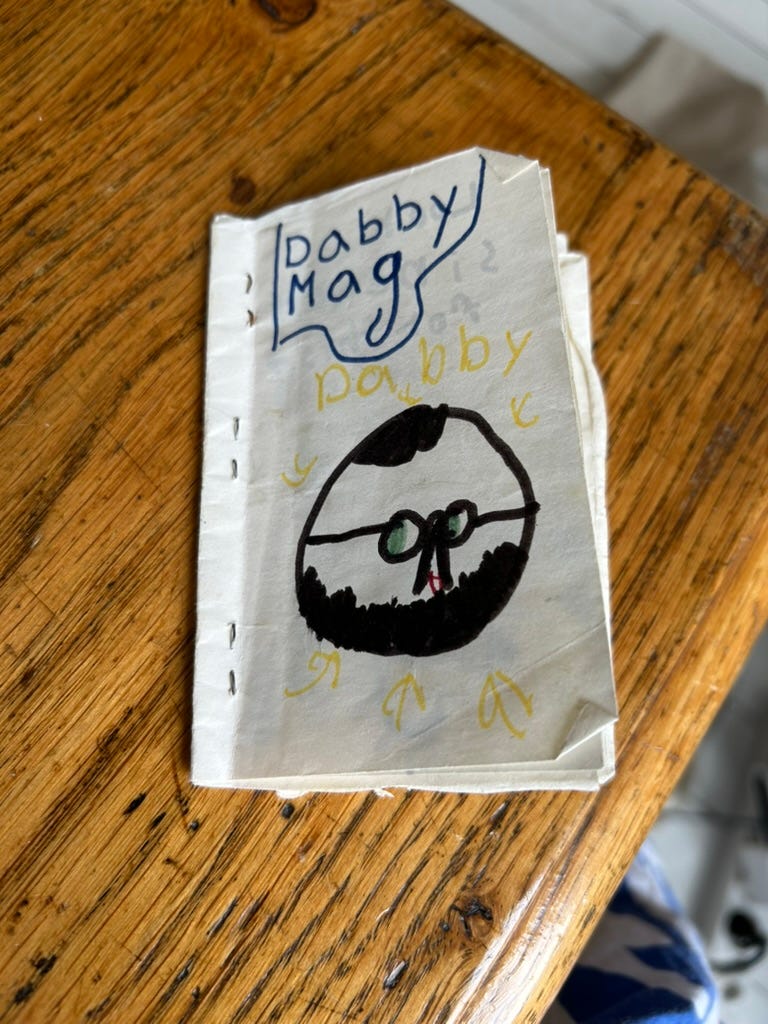

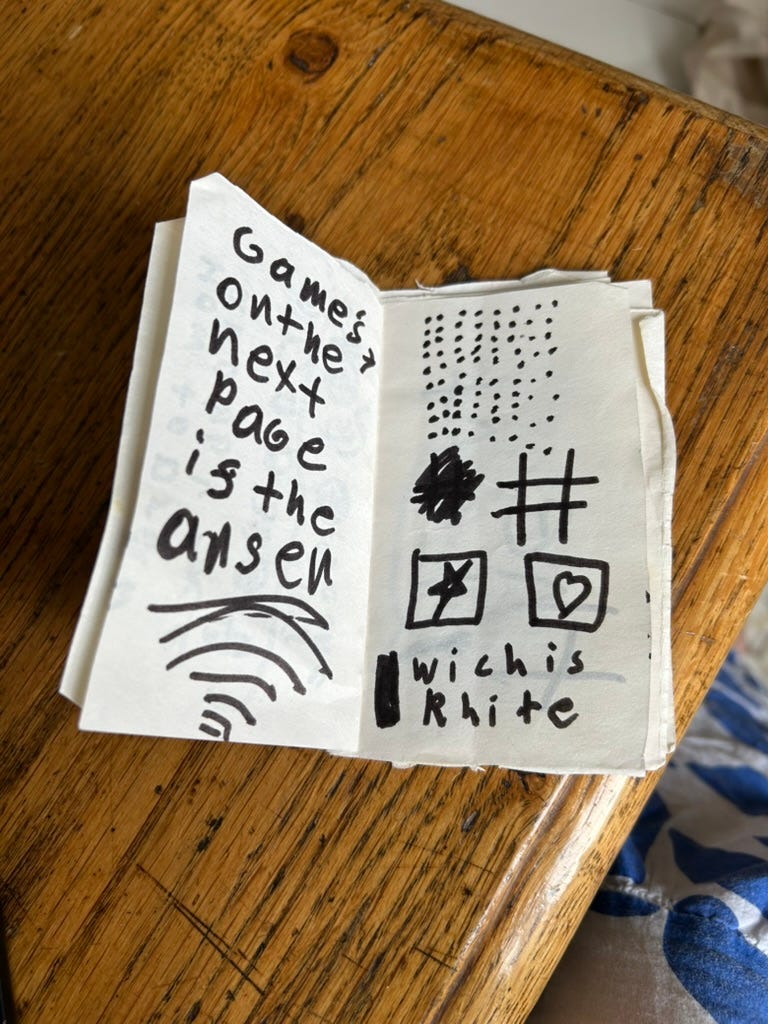

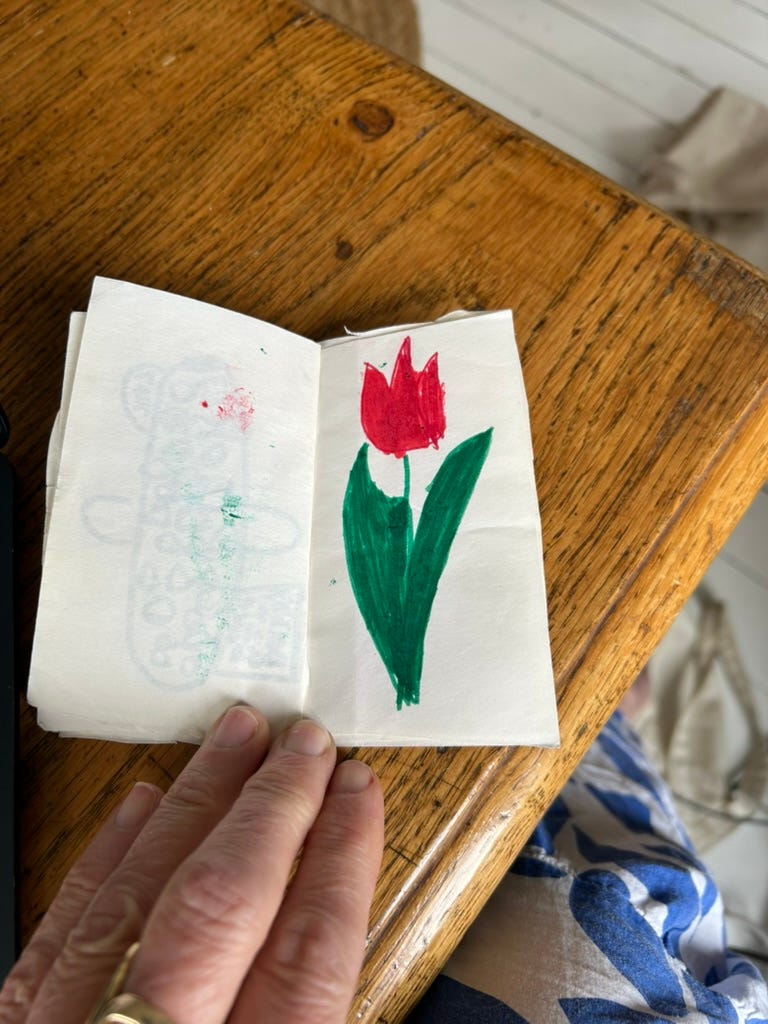

I was genetically engineered to be a magazine writer. I never loved reading magazines, but apparently I always loved making them. When I looked back through my father’s papers after he died, I saw that he had saved a bunch of “magazines” I invented while killing time with my brother and sister at his law office on divorce custody weekends while he forgot he was supposed to be parenting. They were vanity projects dedicated to a caricature persona I developed for him, made out of stapled together xerox paper. They included a front of book section for games and a feature well for shakily drawn pictures of flowers. I suppose they were sort of like the fan pages I was occasionally reading then, except instead of Andy Gibb, it was my dad. (I promise you, I’ve done the therapy.)

I fucking loved being a magazine writer. I didn’t have to pitch a ton because I had longstanding relationships with colleagues who would just call me up and assign me stuff. For subjects like travel, where I would need to generate ideas for editors back in New York who couldn’t be everywhere at once, I’d suggest places I wanted to visit. I managed to get around my lack of expertise by asking questions and staying finely tuned to where I was, all the while being handsomely paid for satiating my curiosity in five-star hotels.

Magazine writing was perfect for my gnat-like attention span and essential dilettantism. I never committed to one field. Because I didn’t want to hem myself in, I played them all: fashion, design, travel, food, architecture, random profiles. I could get interested enough in anything to throw myself into it for a few weeks. Never siloing meant always being a kind of guest star with the PRs rather than a featured player who had to contend with rivalries and headaches. I liked being somewhat unknown to all but a few houses, but still in the mix because I had the backing of a legacy outfit. I didn’t have to accept freebies in exchange for coverage, so I was under no pressure to say something nice about dogshit. It was the perfect combination. No commitments, but I could call anyone and make them talk to me. I was flexing borrowed power.

Nothing was under threat in that arrangement, except the magazine industry itself, which was as comfortable as I was with nothing changing except the news. Oops to both of us.

By definition, FOMO entails a present situation being missed. Missing out means something else is going on at the same time, somewhere else, that you yearn to be a part of. Missing out is different from missing. The magazine party died. If you want a jazzier account of this, with bigger money and fancier stakes than mine, read my Air Mail editor’s memoir.

What I have is not FOMO. It’s nostalgia. Ask yourself the next time you find yourself yearning for something you’re not a part of, because FOMO can be fixed. Just put on your dancing shoes and go to the party. Or FaceTime the friend who is thirst trapping in your feed with your other friends. Join in. There is nothing you can do to remedy nostalgia except try to ignore it as much as possible and then occasionally wallow in it, as I am doing here.

Magazines were my adult adolescence. Maturing means growing roots, going deeper, getting more serious and substantial. It means committing and making moves that are meaningful and considered. I could have tried to move journalism over to this Substack, as so many of my colleagues have done. But because I never wanted to walk down the aisle with one subject matter, I didn’t build the equity or market share enough to make that work over here financially. And my adrenal system was basically shot after catapulting myself to the countryside to remake everything by the seat of my increasingly less-chic pants. Weird that I would become risk averse after taking the biggest risk of my life. Or maybe it makes perfect sense.

The churn of magazine writing was a blessing and a curse. I now live somewhere that moves much more slowly. I look at the same rug every day and watch as Eleanor gnaws my soft yoga blocks down to a nub. The gently moving scrim of nature is never boring, and as ravishing as those spring flowers are, I know they will be back next year, and I will be here to see them. It’s not titillating though it is very gratifying. You can’t have everything.

Still, disappearing from a city at the same time as your byline all but disappears is weird. You wonder if people remember you now that the server that held your best travel clips has been pulped. They probably don’t. Why would they? So you have to find a way to mean something to the people around you, and the people you work with, independent of the ego stroking.

Ghost writing is an intimate job. You’re helping to carry your collaborator’s hopes and dreams to term. You’re holding their hand and clarifying what they really want to say like a shrink. You listen actively and then you imitate their voice as best you can like a shape-shifter. You and your subject spend a year together, not three weeks, during which time you develop trust and navigate challenges and reveal each other’s weaknesses and blind spots for the bigger purpose of a more meaningful book. It is a kind of spiritual union. You need to be aligned in your intentions. I’ve never managed to capture this merging with a romantic partner but I’m a very good writing partner, and so far, I’ve been lucky with my subjects.

This does feel like a more grownup arrangement but for one FOMO-ish reality: you co-write a book that you are immensely proud of but cannot publicly celebrate. You erase yourself. Your name vanishes and you content yourself with the appreciation of the team, and certainly your paycheck, which is fat and reassuring and gives you security. This is normal. The person you are partnering with has the profile and the idea and the brand and the vision that is selling. It is rightfully about them. Maybe it’s like becoming a political wife except that political wives set the agenda, whereas ghost writers mostly serve it. Maybe it’s like being a psychoanalyst? Or a doula, except also one of the parents who moves away after the second act? If any of you reading this are any of these things, let me know.

I savored every single word, Alex.

I related to so much of this, and especially appreciated your reframing of FOMO v. nostalgia. Feel that so deeply. I find myself saying, “I remember when…” or “In my time…” so much and have to stop myself lest I sound like a granny! Times change, and we change. That evolution is such a test of the soul, and can really fuck with our concept of self-worth and want, hut ultimately we are better for it. (Or I like to think so!) Thank you for providing some communal validation in this beautiful piece of writing!