Miracles Can Happen

In which we find Jeannette, and the world opens up once more.

If you come to visit Saint-Maxime, one of the first things you must do is go for a stroll to the lavoir, a tiny, shack-like appendage perched over a natural spring just outside of the village center, where the maximiens of old used to wash their clothes.

On the way to the lavoir, you might say hello to Jeannette. You cannot miss her house. It’s the one with the Holly Hobbie garden filled with elaborate cat trees and a tiny cabin with three picture windows painted all over with flowers, all of which she built herself. On any given day, inside the cabin, you can usually find one of her five cats, each one fatter than the last, lazing around to catch some rays. If they’re not there, then Jeannette might be out walking them and her friendly dog, which she does twice a day, leading the troupe like Saint Patrick in pink sweatpants.

Jeannette scared me at first. She’s gruff and doesn’t put much stock in appearances. If the pink sweats or one of her giant t shirts have some holes, what does she care? Every night after dark she straps on a flashing headlamp and walks the periphery of the forest and outskirts of the village braying like a donkey to get the cats to come in. This caused a falling out with the painter Charlotte, who is usually just getting to bed at that hour and doesn’t appreciate the noise. Cassandre long ago declared herself to be anti-Jeannette, miffed that her dog is almost always off-leash, even if we all know she doesn’t have an aggressive bone in her aging body.

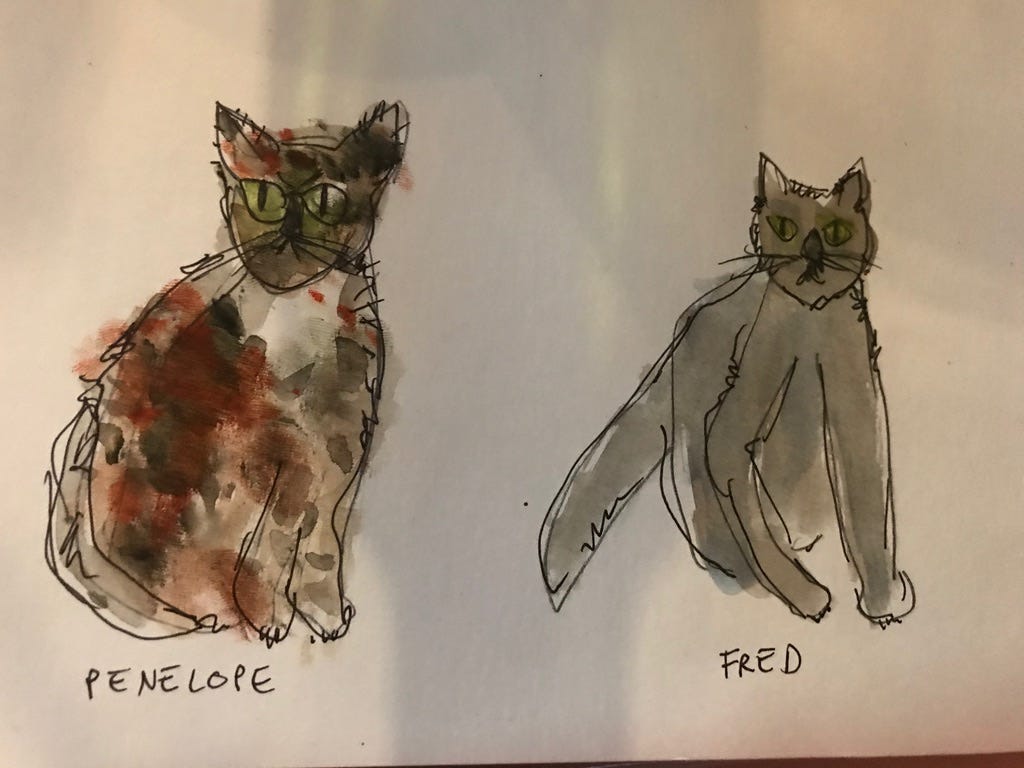

I didn’t have occasion to take a position until Penelope escaped one early autumn night during my mother and Linda’s 2021 visit, and stayed gone for three days. By then, Penelope’s chronic kidney disease had started to really advance, and I had been warned that she may have had some dementia. I imagined her being picked off by a hungry owl or hit by a car, not knowing where she was or where Freddy and I had gone. A hole appeared in my stomach that developed teeth.

In my panic, I reached out to the mayor. She was across the street at the church, in the back offices, where she was sweeping out the literal mountains of barn flies whose colony had clearly gone through multiple generational life cycles. Their corpses crunched under her feet as she maneuvered her giant broom. She told me to send her a picture of the cat and she’d put the word out on whatever network mayors of inconsequential villages must have.

Then I went to Jeannette’s. We had hardly exchanged five words other than when she introduced me to her cats on one of her strolls. She was out in her yard, and I called out to tell her about Penelope. She came right over with a look of extreme concern. She could see I was distraught, and then she was distraught, because even if she didn’t seem to have a lot of time for most people, she really cared about animals.

Penelope eventually wandered back through one of the living room windows that my mother left open, and we returned to something like normal, with me chasing her down once a day to stick a syringe in her mouth, and her brother Fred twice, at exactly eight AM and eight PM, to administer pills for his hyperthyroidism. Going off schedule meant he’d get headaches. As a migraine person myself, I couldn’t do that to him.

So we were in a fairly rigid place as the reality of rurality was starting to come into focus. For most of my adult life, I had grown accustomed to throwing money at problems I didn’t have the time or patience to tackle. In cities, there is usually someone willing to handle what you can’t for a reasonable cash fee. As long as you have a warm enough house and relatively cheap groceries, you can manage pretty much everything else yourself in a small urban apartment.

Twice at around that time, it hit me the hardest that I had gone from being part of a family home to being completely alone: first, when my kitchen was finally finished, and I unpacked all the enormous Dutch ovens that would now mostly just take up space. Second, when I realized I no longer had three other in-house helpers to pick up the cat slack if I ever wanted to spend more than eight hours away. Cassandre and Jean-Yves were conscientious neighbors, but they weren’t going to get up from the dinner table to go pill a cat that didn’t really like either one of them. Nobody gets up from the dinner table in France to do anything. The house might be on fire, it’s still not happening.