Chapter Thirty-Nine: Democracy Was Alive and Well

Back in 2022, at least, Saint-Maxime helped keep the hounds at bay.

Before I launch into our next chapter, which takes place during the first round of the French presidential election in Spring, 2022, I want to thank you all for your patience while I enter the home stretch of a hungy hippo of a deadline. I am working more or less seven days a week til early August. I don’t ask you to tune your tiny violins, just know that as my output here has curtailed, your tolerance is much appreciated.

The election that I write about below was a choice between the extreme right wing and the status quo. It was distasteful for the majority of the country, who didn’t love Macron, but felt constrained to vote for him to shore up against the fascists. Two years on, we’re in an even spicier pickle today. Last month, the far right did better than any other flank in the European parliamentary elections. So, for too many reasons to go into here, Macron has called for a snap parliamentary election that could, for the first time since the Nazis installed the Vichy regime, bring their direct descendants to control the second-most powerful lever of government after the head of state.

Wish this immigrant luck as you enjoy a tale from a simpler time…

If you want to live harmoniously in a small town, the first order of business is not to talk politics. Thankfully France is not a country of lawn signs. Or distress flags, which I am now learning is a thing in some elite quarters in the US. In an underpopulated place that desperately needs to get along, and knows quite quickly if it’s not, you find out where people stand in whispers, not screams. For instance: I had heard that Stan, my immediate neighbor to the north, was an active gilet jaune. But that all played out before my arrival and now mostly he only showed his face on the square when fixing somebody’s car. I had also heard anti-vax noises coming from Angelique from time to time.

I resolutely did not push when the conversation with her made that turn, because when presented with something really objectionable face to face, I knew I wouldn’t be able to hide my distaste. That’s fine in a big city, where you can just duck into a metro or turn to three hundred of your other nearby friends to drown out the discomfort. But in a tiny, tiny place where the electricity goes out a lot and you need help stacking your four tons of firewood before it rains, and it rains 300 days out of the year, open disgust for your fellow maximiens could be the start of something much worse.

It’s the same way that New Yorkers have each other’s backs, because catastrophe looms around every corner in that city, and you just can’t be at each other’s throats. I always wondered why Paris, every bit as on the brink of collapse as New York City, didn’t engender the same esprit de corps. The first time I felt all in it together in Paris was after the Charlie Hebdo massacre, for about ten days, and then in Saint-Maxime most of the time. It was also here that I learned to stick to gardening and the weather. In the Norman countryside, at least these are legitimately hot topics.

I reveled in contrary intel when it was gossip, though, giggling with likeminded neighbors nested in the safety of my fluffy couches, over which older lady in the village routinely slept with younger men, and which other was recently seen wandering the fields in an afterglow, hand in hand with a secret lesbian lover. (We have a lot of older ladies around here, and it seems they get around. Maybe once I cross into the retirement tranche I’ll join them.)

I was getting good at gossip. Simon and Michel, who bought their house many years before I did mine, knew a lot more people in Le Perche than I did. They had friends in other villages and lots of funny, crispy opinions about the most annoying local influencers—of which there were many more than I first realized when I moved out here.

But because I lived in the literal red dot-center of the village all year round, I had started to gather micro-intel even they were jealous of. Cassandre, my Auntie Mame-style mentoress, was a great source for who screamed at whom over what. (The French word for this is tuyau, which means pipe.) There were plots of land for sale that were listed as constructible when they weren’t. There were squabbles over the state of hedges. But Cassandre could also be controversial in her own right. Not only does she have an aristocratic name in a very non-aristocratic community, but she militated against early church bells and complained when the town parking lot that abuts her backyard got too live from the pétanque club. She was willing to make a scene.

To my mind, a lady of a certain age who has paid her dues in life and raised four upstanding members of society is entitled to some quality of life guff, but village rules are different. Any wave you make can come back to engulf you. Meaning: when her name was mentioned among maximiens that were less intimate with her than I, there was a tone. I made like I didn’t hear it and kept smiling. I was the foreigner, after all. I could pretend to miss everything, benignly, even if everyone saw that I went over to her place at least once a week for drinks and snacks and tales. Not my problem. Not my business. What did you say? Oh, I thought you said something else.

In a previous chapter I mentioned how we villagers are constrained by a kind of virtuous peer pressure to show up at town meetings. If I was in town, which I usually was, and something was happening en masse in the conference room at City Hall, I was there, rain or shine, to show I was not some posh vacationing squatter. Everyone knew I was useless—I couldn’t haggle for ass sausage discounts, nor grease any paperwork wheels downtown—so they didn’t really expect much of me. But I was there.

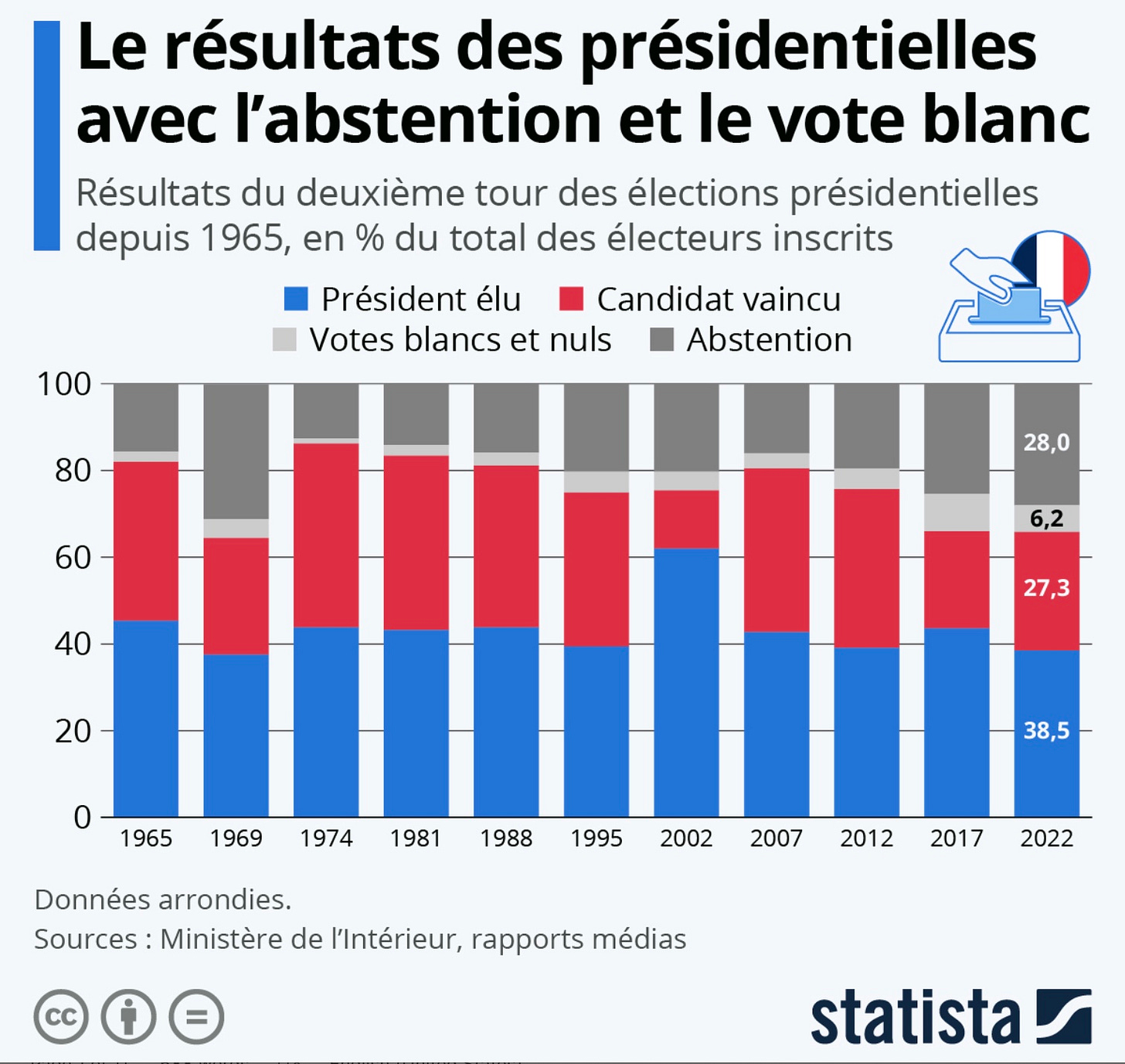

Which is why nobody was surprised to see me rock up to City Hall to attend the vote count for the first round of the election, even though, as a non-citizen, I couldn’t participate myself. I’ve always been fascinated by the high turnout and general rigor of French elections. That they vote in two rounds is incredibly sensible, allowing for strategic alliances to form for the second round, when you’re down to just two postulants, and somebody unacceptable might need to be eliminated. That had already happened in France in 2002, when Marine Le Pen’s deliriously bigoted father Jean-Marie made it to the second round against the center-right Jacques Chirac. And again in 2017, for Macron’s first election, when Marine had the honor, and, thank God, bombed.

As it was still the first round, this vote was simply to shake out the weirdos: the lesser blood-and-soil fascists Eric Zemmour and Nicolas Dupont-Aignan, various subtle flavors of communist, and quixotic ego campaigns like that of Paris mayor Anne Hidalgo. Once the dross was eliminated, we’d see exactly how bad it was going to be for Macron two weeks later, when it came down to the final contest. This time, we knew that Le Pen and her party had a larger number of sympathizers nationally, and Macron’s first term didn’t win him any converts.

I was on a knife’s edge, assuming every member of my village was voting for her. The center-periphery divide in my adopted country is even more darkly drawn than in the US, and Le Perche does not smell like opportunity. Other than the influencers, who probably smelled like locally grown lavender, Le Perche smells like the same cow manure it did three generations ago. Everyone stuck here knows the action is somewhere else and they are not celebrating over it. They’re pissed, and generally, protest is a common way for them to be heard.

The audience numbered about fifteen. Other than Angelique and me, it was elderly residents. In the seats at the table facing us were the mayor, and Benoît the former king of the party planning committee, because of course, as well as a much older lady I didn’t recognize, and Stan and his mother, in a civic turn I didn’t expect but was glad to see. Except for a padlocked plexiglass box filled with small, Wedgewood-blue envelopes sitting on the table in front of them, the room’s décor hadn’t changed since I was there for the party planning committee. But the air had a different weight. It was a combination of hope and gravity. Civic duty was in the house, so nobody chit-chatted as we waited for the hour to strike 7 pm, when the polls officially closed.

The moment they did, the mayor made a brief acknowledgment of us. “You are here as members of the public to observe, as is your right.” I was part of a transparency squad, which I was proud to be. “Allez, c’est parti!” the mayor said, and with that, counting got started. Out of 188 possibles, 144 people voted. Points for Saint-Maxime’s engagement. Each envelope was opened, the vote was announced, and then it was validated once more by Stan. Everything was anonymous. The much older lady tallied each result and about halfway through, she started getting confused and falling behind, and there were some stern whispers that grew to cleared throats and calls to slow down and let her catch up. As the numbers mounted, there was a shocking vote for the Green Party’s Yannick Jadot, exceptionally unpopular in the countryside, and even one for Hidalgo. Another elderly madame in the audience openly cheered every time Jean Lassalle, a “radical centrist” (huh?), got a tick, for a total of five. I guess if you’re going out on a limb like a maverick, it’s reassuring to declare yourself right down the middle. I figured she knew one of his cousins.

At the end of the count, Marine Le Pen got only 34, Zemmour six, and dictator-friendly leftist Jean-Luc Mélenchon, a total of 19. Macron, on the other hand, came in for a whopping 55. Macron has done little to make us cheer for him. But I found it salutary that there was less discontent in Saint-Maxime than I imagined.

Good to know for the upcoming contest, happening on the 30th of June and the 7th of July, whose count I will absolutely attend once more. I’m not optimistic, but then again I rarely am. I will keep you posted.

Vote counting is compelling like a jury trial. Awaiting the next round is sort of like anticipating the next mini-series episode. Do tell why Macron is so disappointing though. From here he seems like such a nice young politician. No rush. When you have time.