Chapter Thirty-Five: Holly, Somewhat Jolly

In which we cobble together a new kind of Christmas Spirit.

By the close of 2021, the world was still a mite too COVID-y for me to get on an eleven hour flight home to Los Angeles for the holidays, as I normally would have. Confinement was more or less behind us all, but Southern California’s highly suggestible antivaxxers had pumped just enough defiance into LA’s already narcissistic atmosphere to make the city a very bad infection risk. Masks? What are masks?

I was looking to slide over to one of my new Saint-Maxime friends’ place for the big day, to try to replicate some sense of family. Cassandre would have her four grown kids home, and her grandchildren, and I knew I would be welcome if I had no place to go.

Even if I spent the better part of my adolescence as a loud and proud dialectical materialist, I am very susceptible to the Christmas spirit. This does not mean that I get into decorations, like the shopworn ones that went up in Saint-Maxime. (The village party planning committee hauled out giant multicolor lights—shudder—and stuck a stuffed Santa in a sleigh at the corner of the church. He ended up hunched over as if he had just had a heart attack or too much mulled wine.) This does not mean I can stomach classic American carols, either, for God’s sake, which my siblings and I started vetoing once we got old enough to share dominion over the stereo. Sorry to Johnny Mathis. My mother will never understand how all three of her children ended up so utterly devoid of sentimentality.

We have our own rituals, though. The season only truly begins when all three siblings are present, starting to crest into a sugar high from dusting half of a two-pound assortment of See’s nuts and chews, and we strike up Teddy Van and Akim’s “Santa Claus is a Black Man.” The song was recorded in 1972 by Van, a talented musician and producer, and his five-year-old daughter, at a time when Black people were still almost entirely excluded from Christmas imagery. (Here is a great story about it that will fill out the details even more. )

Our lily white family found the song on the magnificently louche compilation, A John Waters Christmas, a gift from one of our mother’s closest friends, maybe twenty years ago. This friend had picked up on the carol wars going on in the house and wanted to lighten the mood. From then on, every time that Akim’s first “Hey,” rang out to open the song, our mother rolled her eyes and dropped her head in her hands. That’s how we knew we were really home.

That’s how we do family bonding. We also do get off on the chance to compose and execute a complicated meal together, exchange goofy gifts, see friends and extended family who knew us when were still wetting the bed, and remember that we all still love each other quite a lot.

The only other time in my life that I voluntarily skipped out on Christmas in LA was when I was in my early 30s and living in New York City. I was feeling very autonomous and didn’t want to dive into “family drama,” but to construct an adult version of the holiday with chosen family. I ended up out to Christmas dinner at a Mario Battali restaurant with a dear pal and I had never felt so displaced and miserable. It wasn’t the friend’s fault, it was ordering off a menu, and nobody to do the “I can dig its” and “right ons” along with Teddy Van in the interludes.

So there would be no Teddy Van for me in 2021 either, and I was growing apprehensive about it. Then Charles sent up a very sad flare. He needed to come back through France over the holidays, because his friend Terrence’s cancer had taken a turn for the worse, and it was time to put him in palliative care. Terrence had a bitter ex-wife, a fairly useless daughter and a very nice girlfriend, but nobody can problem solve like Charles, a crisis management savant. I was saddened by the news. I didn’t know Terrence as intimately as Charles did, but I adored him. Still, I was selfishly happy that I would have someone hanging out at my place who was as much of a brother to me as my own.

Terrence was by then based in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, a tony suburb west of Paris convenient to the hospital in Neuilly, and also, more or less, to Saint-Maxime. There was space for Charles to crash there, but Terrence’s girlfriend was also in residence. They liked each other quite well, but helping a soul brother die is harrowing and intense, so naturally Charles would occasionally need to flee the scene if things got too crowded or he got too exhausted. We planned for him to come out to my place whenever he needed to, TBD.

Once he arrived in country and got set up in Saint-Germain, the stories Charles told me from Terrence’s bedside were chilling. Pain management was flaky and sometimes simply disrespected. There was not a lot of communication and no real patient advocacy.

I had some experience with palliative care, and it was not this. My father died of very aggressive prostate cancer in 2005. Since his diagnosis was terminal from the beginning, the Boulder, Colorado hospice care association stepped in immediately. My father wouldn’t have treated himself with chemo even if the prognosis allowed for it, because by then he was far too New Age and all-knowing to accept anything other than herbs and juice cleanses and coffee enemas that did nothing. At least there was no reason to have an argument about it. Hospice made sure his pain meds were delivered on time, and they were present for any side treatment he needed for his comfort—one thing they don’t always tell you is that cancer creates a mess of secondary infections.

The hospice workers also acted as chaplains of a sort, informed by a kind of fuzzy spirituality that included a lot of crucial tips on dying gleaned from their extensive experience with it. They had a checklist of signs for when the slide down starts getting irrevocably steep, usually a few days before the end: my father would go inward, they said, silently reviewing the details of his life. By this point he would likely be entirely uncommunicative, and we should expect that. In addition to a kind of basic map of the experience of death, they provided a portable hospital bed and, eventually, a morphine drip, to my father at home so he could remain where he was most comfortable.

The hospice counselors also provided the survivors, who are anxiety-ridden and heartbroken and chaotic, some valuable protocols. I went out for visits to Boulder from New York, where I was still living in 2005, as often as I could, and the team offered us counseling together. They had us all sign a paper committing to respecting my father’s wishes for how he wanted his actual passing to go. He filled out a detailed questionnaire that was mostly about comfort directives. “Do you want music playing or poetry read to you as you pass? If so, which?” (Rachmaninoff, he said, even though he never thought he was actually going to die until the very end.)

Hospice was present, they were wise, they were patient, they were informative, and they were respectful. We couldn’t have gotten through the wildness of losing our father as serenely as we did without them.

So when Charles told me how it went in France, I was terrified, because chances are, France is where I will end up kicking the bucket too. The human factor in Terrence’s care was non-existent. Checklist to prepare survivors? What is that? Terrence was by then almost entirely residing in the hospital, and if you’ve never been in a French hospital, know that socialized medicine means socialist comfort. It’s not terribly pleasant. (It’s also free and excellent. This is not me complaining.) So Terrence was not getting any kind of institutional hand-holding nor experienced intelligence around how his death might go, nor much respect for his dignity, which was really crushing, since he was always a shy and somewhat modest man.

Thankfully for Terrence and his family and Charles, the period of true decline was swift and short, which meant that Charles was back at mine for Christmas with no need to stay on call, and lots of need to collapse and comfort eat. These are two things I had by then realized that my house specializes in.

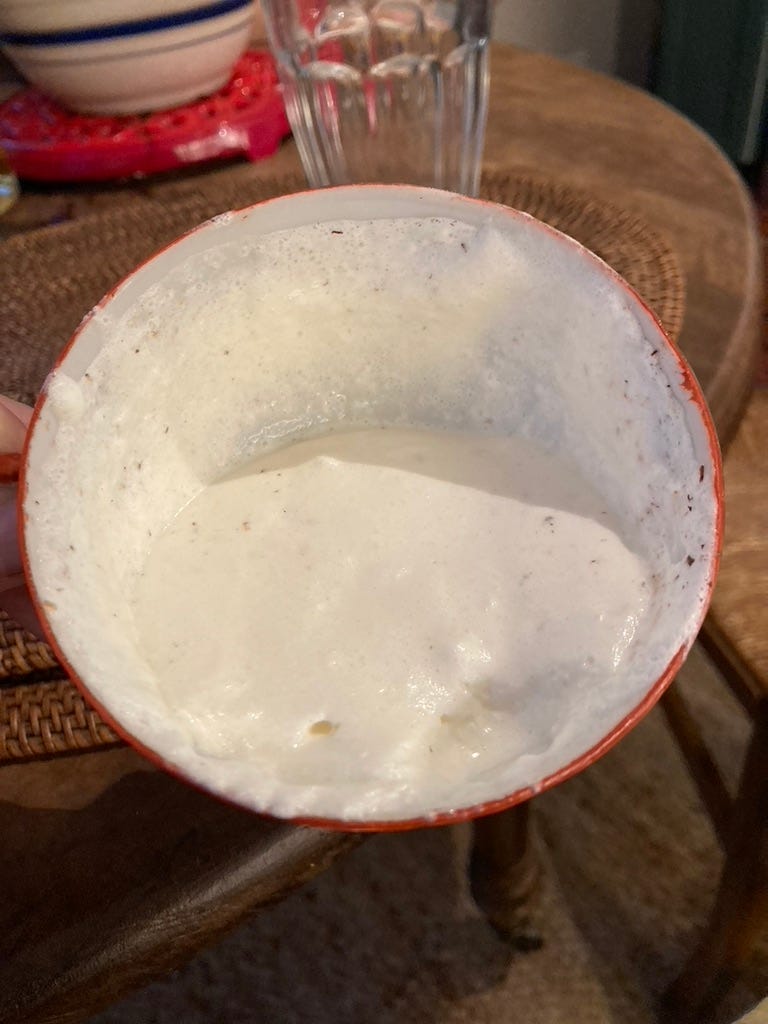

We got our priorities in order: first came a big shop for Kit Kat Balls, which, as far as we know, exist in France only. (For the intense crunch and slight saltiness, they blow doors off the original.) We stocked up on ingredients for Martha Stewart’s five-alarm-boozy egg nog, a luxurious classic which always made us feel a bit like Sunny von Bulow in the best way possible. (If Charles and I couldn’t be swaddled in the cashmeres that Glenn Close, as Sunny, wore in Reversal of Fortune, for a short time, that boozy blood sugar crisis in a bowl made us feel like we were.) We roasted a guinea fowl, whose leftovers became taquitos with suitcase corn tortillas that we garnished with a large pot of Charles’s refried beans.

Charles and I have cooked many meals together, and we both feel home in our stomachs before we feel it anywhere else, so being together in a kitchen anywhere, at any season, we are usually in fifth gear. When we weren’t frying or folding something into something else, we took brisk walks in the woods to air out his head.

When he finally felt up to some socializing, we popped over to Cassandre’s, whom I was discovering to be an excellent person to go to for comfort in existentially harrowing times. Her own life had dealt her quite a few blows: she had lost two of her own brothers to drugs and AIDS when they were both far too young. And just a little over a year before she and I first met, she had lost her boyfriend, a wild and wolfish Dutch painter, to a massive stroke.

She made meatloaf and we brought over a baked lemon pudding that we made from a New York Times recipe for the first time. (Kind of meh.) We drank supermarket red and she regaled us with the time one of her uncles took her when she was a teenager to an opium den in Mauritius, where some of her family lived, just so she could see what was going on. And then the time one of her other uncles was having an affair with her classmate. And so on. The cure for what ails you when you’re going through a shocking time can sometimes be as simple as stories even more shocking than your own, told with wit and flair. It’s a subtle signal that this too, whatever it is, shall pass.

Charles hung around as long as he could stay away from work, helping Terrence’s girlfriend with her part of the bureaucracy and backing her up when Terrence’s ex threatened to flood the zone with bad vibes. I was in no hurry for him to go back to LA.

What a pleasure, sprinkled with the occasional moment of chagrin, it is to be Alexandra’s mom. I look forward to every chapter, and eat up every word. She never disappoints.